What kind of steel is that knife made of? I have asked that question myself while perusing the tables at knife or gun shows. It is really a useless question if you stop and think about it. It might be 5160, O1, 440-C, ATS 34, D-2, or any number of suitable steels, but in the end does it really make any difference? Probably kitchen knives see more abuse and use than any other knife you’ll ever buy. Did you ask the lady in the house-wares department what steel they were made of before you bought them? Being the male chauvinist that you are, probably not, because they were for the wife and you figured she wouldn’t care. More than likely you looked all of them over, picked out the prettiest ones, something in a middle price range, and cashed out.

Now you are wondering, “Is my steak really that tough or is the darned knife dull again”. What do you expect, you have been using it for a year and never touched up the edge. It was probably made from some low carbon stainless and tempered to a spring temper to ensure it didn’t break. In the past year you’ve used it to peel potatoes, slice cheese, and chop frozen chicken legs apart. I wouldn’t be surprised if you even used it to open a paint can or tighten a screw every now and then.

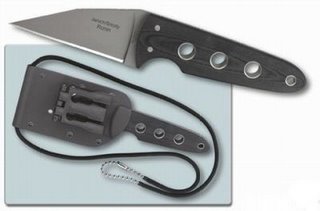

How many times have you used that custom tactical knife that you paid $450 for? Come on now be honest. Have you cut open any 55 gallon fuel drums like the advertisement showed? Did you go out in the back yard and dig a fighting hole, build a dead fall, or take out a few sentries with it? Hmm, not likely. Before ordering it you read every article in the top knife magazines on blade steels and tempering processes. Now you can spout out the composition of every steel known to man and its optimum rockwell hardness, but does it really matter? Despite the number of times you have not used it you specified that it had to be made from one of the latest exotic blade steels and be triple sub-zero quenched. Who am I to pick fun at you, haven’t I gone through the same scenario myself?

If you’re buying a factory made knife, buy from a reliable company then you can be confident that they are using the appropriate steels with compatible heat treat processes. Personally I am not a big fan of the modern tough stainless steels. Some of them are damned near impossible to sharpen and once dull only a belt grinder will restore the correct geometry and produce a sharp edge. Many of these steels are never truly razor sharp even with the best of edges. With some of them you could spend a lifetime rolling a burr from one side of the blade to the other. This is the price you pay for not having to take care of your knife. Remember that the use of these carefree steels was driven by customer demands and laziness.

If you’re buying a custom knife then you should be buying from someone reputable, someone with a track record for quality workmanship and materials. Many custom makers offer a choice of steels to satisfy customer’s whims but I would recommend sticking with the maker’s preference. It never hurts to ask for references or links to articles about the maker and his products. If the maker does his own “in-house” heat treat it would be a good idea to stay away from the real exotic steels with complex heat-treat requirements. On a side note, I have watched in fascination as the late Bill Moran hardened and tempered a Bowie blade for me with an acetylene torch and a bucket of quenching oil.

When buying from a custom knife maker you might want to ask about his policies on customer satisfaction and returns. You might even want to get it in writing. One time I bought a used custom tactical knife and when it arrived it was as dull as the village idiot. I tried every sharpening device known to man and never could put an edge on it. After several unanswered emails to the maker I resold it at a loss. I will not own a knife that won’t sharpen. Not too long ago I owned a Bowie made by one of the masters of that genre. It would not sharpen either and so I traded it off for a Randall model 14. I may regret the passing of that knife because of the name it bore but certainly not for its lack of cutting ability. A knife maker should stand behind his product one hundred percent unless it has been abused. Shame on you if you were the one to abuse it!

Based on my own personal experience here is a list of men whom I bought custom knives from that were delivered razor sharp. In no special order they are;

· Gary Bradburn

· John Greco

· Kent Hicks

· Chris Peterson

· Brent Sandow

· Mr. De Leon

· R.J. Martin

· Dale Larson

· Bud Nealy

· Craig Barr

· Brett Gatlin

· Larry Harley

For the most part I have no idea what steel these makers used. I know

the men and they know their trade. That is good enough for me. That doesn’t mean I won’t read the next article on the newest exotic steel, it just means that when I order my next custom knife I still probably won’t ask, “What steel is that knife made from?”

David Decker

White Shadow Dojo

Now you are wondering, “Is my steak really that tough or is the darned knife dull again”. What do you expect, you have been using it for a year and never touched up the edge. It was probably made from some low carbon stainless and tempered to a spring temper to ensure it didn’t break. In the past year you’ve used it to peel potatoes, slice cheese, and chop frozen chicken legs apart. I wouldn’t be surprised if you even used it to open a paint can or tighten a screw every now and then.

How many times have you used that custom tactical knife that you paid $450 for? Come on now be honest. Have you cut open any 55 gallon fuel drums like the advertisement showed? Did you go out in the back yard and dig a fighting hole, build a dead fall, or take out a few sentries with it? Hmm, not likely. Before ordering it you read every article in the top knife magazines on blade steels and tempering processes. Now you can spout out the composition of every steel known to man and its optimum rockwell hardness, but does it really matter? Despite the number of times you have not used it you specified that it had to be made from one of the latest exotic blade steels and be triple sub-zero quenched. Who am I to pick fun at you, haven’t I gone through the same scenario myself?

If you’re buying a factory made knife, buy from a reliable company then you can be confident that they are using the appropriate steels with compatible heat treat processes. Personally I am not a big fan of the modern tough stainless steels. Some of them are damned near impossible to sharpen and once dull only a belt grinder will restore the correct geometry and produce a sharp edge. Many of these steels are never truly razor sharp even with the best of edges. With some of them you could spend a lifetime rolling a burr from one side of the blade to the other. This is the price you pay for not having to take care of your knife. Remember that the use of these carefree steels was driven by customer demands and laziness.

If you’re buying a custom knife then you should be buying from someone reputable, someone with a track record for quality workmanship and materials. Many custom makers offer a choice of steels to satisfy customer’s whims but I would recommend sticking with the maker’s preference. It never hurts to ask for references or links to articles about the maker and his products. If the maker does his own “in-house” heat treat it would be a good idea to stay away from the real exotic steels with complex heat-treat requirements. On a side note, I have watched in fascination as the late Bill Moran hardened and tempered a Bowie blade for me with an acetylene torch and a bucket of quenching oil.

When buying from a custom knife maker you might want to ask about his policies on customer satisfaction and returns. You might even want to get it in writing. One time I bought a used custom tactical knife and when it arrived it was as dull as the village idiot. I tried every sharpening device known to man and never could put an edge on it. After several unanswered emails to the maker I resold it at a loss. I will not own a knife that won’t sharpen. Not too long ago I owned a Bowie made by one of the masters of that genre. It would not sharpen either and so I traded it off for a Randall model 14. I may regret the passing of that knife because of the name it bore but certainly not for its lack of cutting ability. A knife maker should stand behind his product one hundred percent unless it has been abused. Shame on you if you were the one to abuse it!

Based on my own personal experience here is a list of men whom I bought custom knives from that were delivered razor sharp. In no special order they are;

· Gary Bradburn

· John Greco

· Kent Hicks

· Chris Peterson

· Brent Sandow

· Mr. De Leon

· R.J. Martin

· Dale Larson

· Bud Nealy

· Craig Barr

· Brett Gatlin

· Larry Harley

For the most part I have no idea what steel these makers used. I know

the men and they know their trade. That is good enough for me. That doesn’t mean I won’t read the next article on the newest exotic steel, it just means that when I order my next custom knife I still probably won’t ask, “What steel is that knife made from?”

David Decker

White Shadow Dojo